Developing Sangrampur Village

Research, Design and Reccomendations

From 2012 to 2017 I have conducted various research projects focusing on development in India. These projects can be broken down into 3 completed phases.

Phase I:

Role of Entrepreneurship at the grassroots level

Phase II:

Gaps in energy infrastructure and services and impact on rural grassroots economy

Phase III:

Gaps and challenges to public education in rural schools

Role of Entrepreneurship at the grassroots level

Phase II:

Gaps in energy infrastructure and services and impact on rural grassroots economy

Phase III:

Gaps and challenges to public education in rural schools

Explorations and data from Phase I and Phase II were used to create a community center design for one of the villages which were a focus of the research. The design centers on using public space in the village center to create social and functional spaces that support educational, vocational, nutrition, and energy needs of underprivileged communities within the village.

I was born in Uttar Pradesh and lived in Sangrampur for the first 5 years of my life. Close family continues to live here. I have visited Sangrampur often and my personal proximity has allowed me access and insight usually invisible to outsiders. Alongside 5+ visits since 2011, I have spent 3+ visits on focused research work including interviews, site visits, surveys, and secondary research.

Understanding Sangrampur continues to be an ongoing effort. The overarching goal continues to be to give back to the community in an empowering and sustainable way. Furthermore, as a microcosm of a rural Indian community, Sangrampur offers the opportunity to learn about how rural development might be understood and approached in other parts of the country.

Phase I: Research and Insights regarding grassroots development

Phase I was a series of interviews across the village to identify pockets of entrepreneurship. While phase I was not explicitly focused on identifying social and economic dynamics, the outcome gave insights regarding the same and shaped future research.

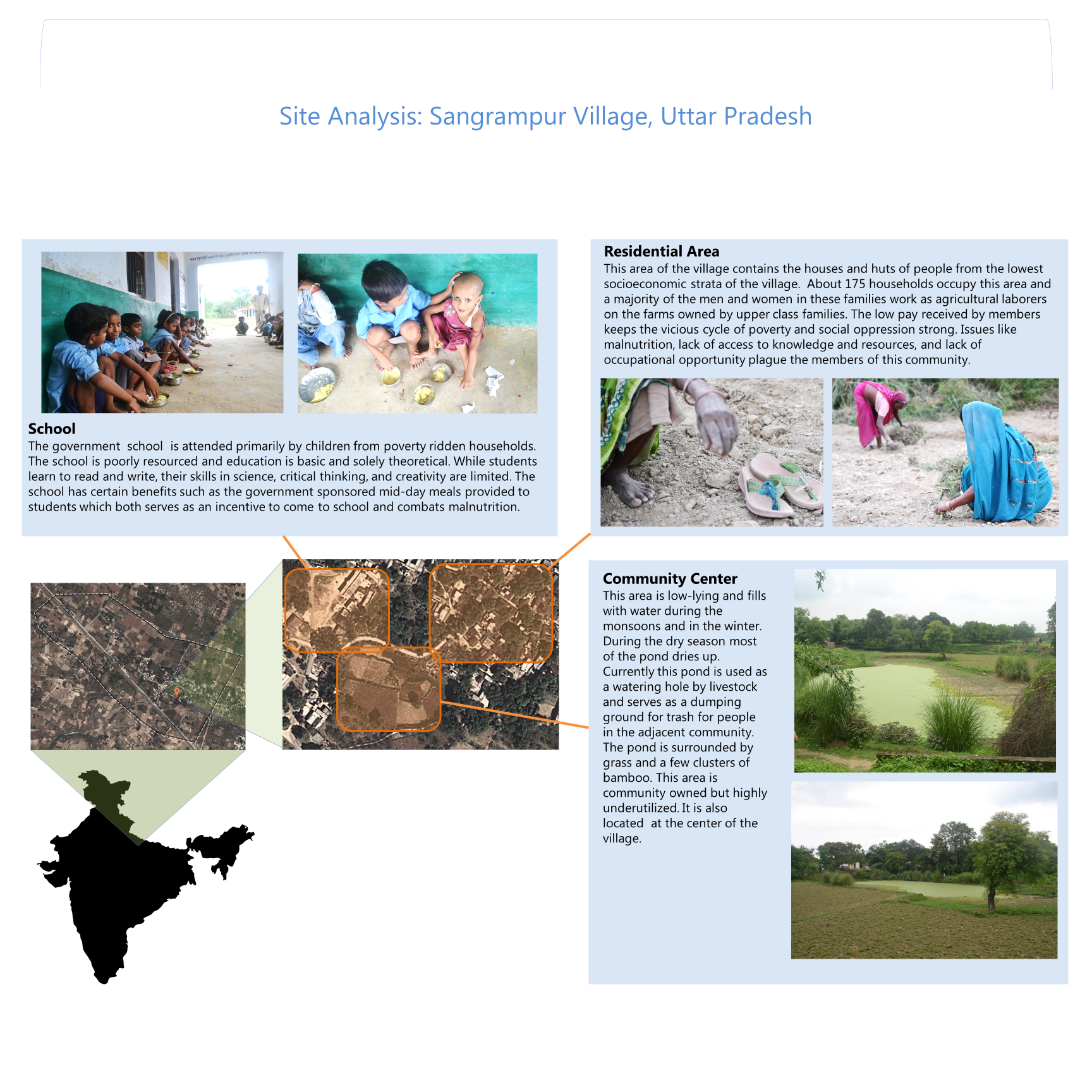

Key insights were as follows: Sangrampur is a heavily agricultural community with most land held by privileged caste “Thakurs” who employ socio-economically underprivileged communities in agricultural and other work. This dynamic is also preserved in local politics, even when federal quotas require members of traditionally underprivileged castes as they lack resources and time to put towards campaigning and resources. Often public funds are also diverted toward private causes, impacting areas such as public schooling. While government resources have made a visible difference in education and infrastructure, there is substantial room for change in social structures and the development of public resources. Development of shared resources, supplementary education and vocational training could help bridge some of these gaps.

Phase II: Research and Insights regarding energy needs and infrastructure in rural Uttar Pradesh

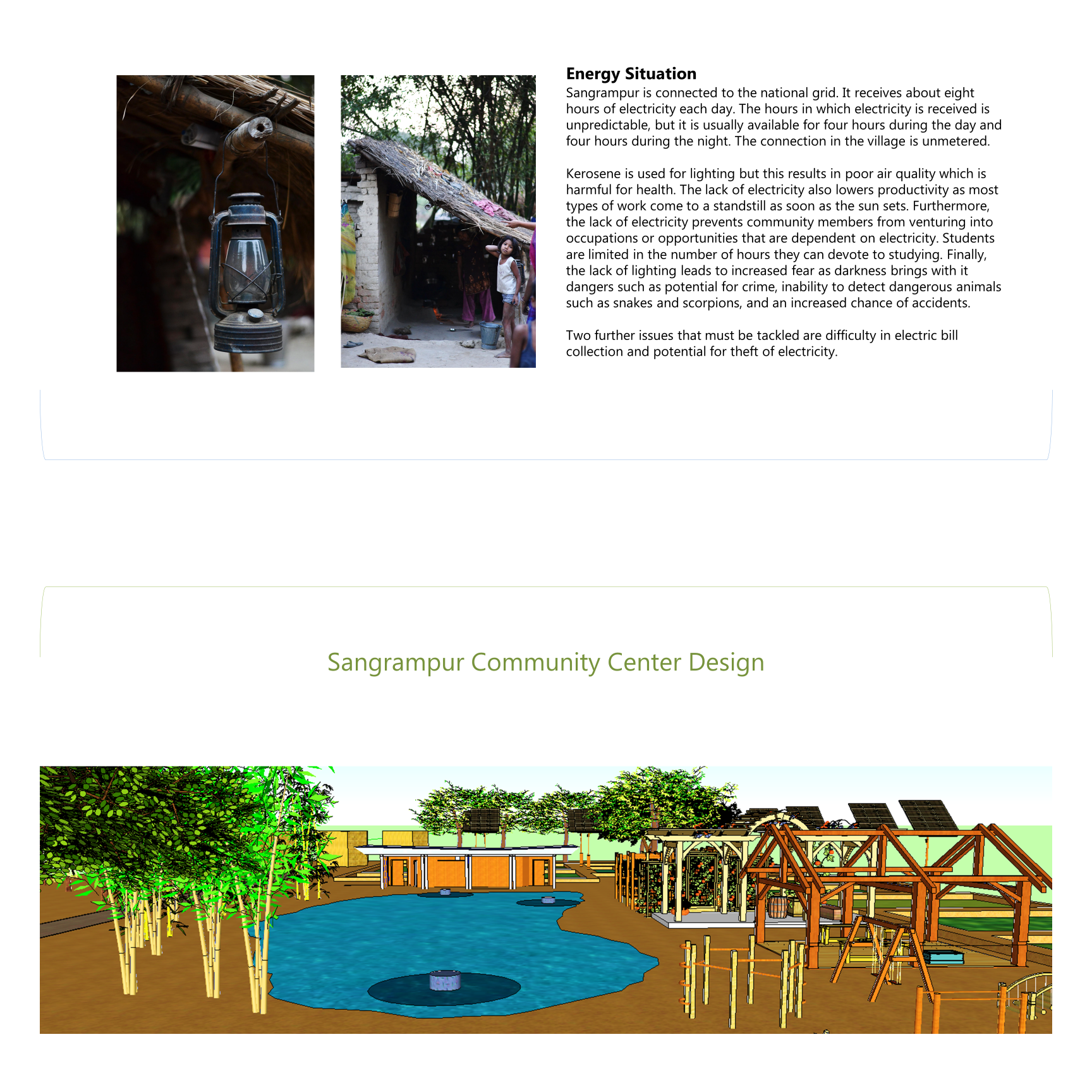

A critical ingredient for development is access to energy. One of the traits of what are labeled “developing countries” is the lack of access to energy. In India urban centers are likely to be connected to the grid and have access to electricity for large parts of the day. Rural areas, however, get limited electricity ranging from 6-18 hours a day, depending on whether it is election season or festival time. For parts of the world with access to electricity at all hours, electricity becomes something taken for granted, a reliable fact of life. For various parts of rural India, large parts of the day are spent waiting for electricity to be back on so people can turn on the fan, use a heater, study, work, irrigate their land, iron their clothes, grind their flour, charge their phones, and maybe watch some television. For the scope of this research, the focus was on identifying the causes and impact of gaps in energy services in a rural setting. The purpose of this research was to explore whether alternative energy system could help fulfill the local needs.

In India, the energy industry has largely operated in the public space, with segments of the supply chain such as generation being privatized. The public sector infrastructure and processes have long failed to curb inefficiencies. As of today, there are strong efforts at reform and privatization. At the time of this research, privatization was still only a suggestion. However, alongside privatization, this research explores the potential for microgrids and decentralized energy systems to optimize the use of local resources, create self-sufficiency, and spread awareness about conservation of energy.

To conduct this research I interviewed people across various socio-economic categories and occupations in 5 villages in central Uttar Pradesh over 2 months to identify their needs and challenges. I also visited the NTPC (National Thermal Power Corporation, Unchahar, Uttarpadesh) where I interviewed various individuals (managers, engineers, directors) to understand systemic issues at play in the energy space. The findings informed the design of a community center for Sangrampur India.

Key findings were as follows:

1. Electricity is treated as a free good leading to wastage and theft

Subsidized rates have created expectations for free or cheap electricity. Electricity is largely talked about as a human right to be provided by the government. Often, interviewees suggested that electricity is available extensively prior to elections when the incumbent wants to use their position to secure the next election. Furthermore, election platforms often contain promises for increased access to electricity and cheap services. When politicians make promises without accounting for the state of the current budget and infrastructure, this links these services to the government in the mind of the consumer. This has created the ground for a tragedy of the commons that leads to rampant wastage and theft when electricity is available.

2. Public distribution systems create a bottleneck in energy system

The energy system in Uttar Pradesh has struggled because even as there is ample capacity to generate electricity, distribution infrastructure is lacking and the public sector is unable to pay for electricity as they struggle to collect payments from end consumers. Usage of technology has recently helped alleviate some of this burden but additional infrastructure is critical to ensure that distribution does not become a bottleneck. Furthermore, high distribution losses indicate the need for additional metering and use of underground cables to create infrastructure that will serve local needs in the long term.

3. Lack of lighting creates safety hazards

Rural areas are poorly lit, with tracts of wild and agricultural land around them. Lack of electricity reduces people to carrying on with lanterns and other flame-based lamps that provide very little light. This not only hinders movement but creates unsafe environments around rural areas. This disproportionately effects women who are limited to their homes by calls for safety. The irony being that the very efforts to keep women and children safe imprisons them, and these spaces, constantly devoid of women become safe spaces for misogyny, and violence.

4. Availability and access does not fit use patterns and needs

In developed regions the steady availability of electricity has created heavy reliance of electricity, contributing to large quantities of pollution and waste. In rural areas, however, often people responded that 24 hours of continuous supply is not a need. Most people defined their needs differently: they wanted the schedule to be transparent and reliable. On average people suggested the need for 12-16 hours of electricity to be able to function efficiently. The expense of unreliable electricity was higher than that of limited hours of electricity as farmers were forced to hire expensive diesel engines to carry out irrigation at the last minute or to install generators to carry out business. Lack of reliable electricity schedule and supply also reduced the incentive for people to pay for a connection. Most people (except a few from the lowest socio-economic communities) mentioned that they were willing to get metered and pay for electricity use if theft could be prevented and if electricity was provided at regular hours and at regular intervals. People indicated that electricity was a resource they could not control or rely on and this led to loss and hesitation in investing further in local businesses.

With the above in mind, the community center design focused on creating self-sufficient energy infrastructure to supplement the grid. This would create public spaces where electricity could be available for extended hours, allow for public education, and create jobs and opportunity for vocational skill development in the energy space.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank Babson College, Olin College, Weissman Program and Family, Brian Duggan, Melissa Shaak, Abigail Mechtenberg and Martin Mechtenberg for their support and guidance in this research and design project.

I would like to thank the residents of Sangrampur village, officials in NTPC, and in government administration in Sultanpur, UP for sharing their experiences with me.

Cargo Collective 2017 — Frogtown, Los Angeles